There is no desire more natural than the desire for knowledge. —Michel de Montaigne

My stay here has taught me many things — above all to judge severely the patients and the doctors, the patients more than the doctors. —Raymond-Raoul Lambert, Drancy, 10 October 1943

The future belongs to ghosts. —Jacques Derrida

Insecure in my semiconscious sense of entitlement, I fumbled with that old Rollei as a tableau of tourists posed for their Parisian portraits. The woman on the right did not want to be photographed and rushed by. The woman holding a shopping bag adorned with 18th century iconography glared at me. I pointed to the painter drawing her and made a shush sign with my finger to my lips. Must not distract the artist! She looked up, exasperated. No match for her, I tripped the shutter and hurried away.

A blind man stood patiently at his post when I asked his permission to take his picture. “I am not a tourist,” I explained. “Quelle surprise,” he looked at me. “Tourists snap my picture without asking all the time. They stand in front of me and stick their cameras in my face. They don’t say anything to me and think I don’t know they’re there. But I see them, in my way. Sure. Go ahead and take my picture. Turn me into a postcard. Stand over there and wait for the rich ladies to come out. When they see me they’ll speed up and pretend I’m not here, so they don’t have to give me any money. I feel the breeze from their fur coats and smell their perfume. I hear them too. Every Sunday. Make sure they’re in the picture with me. They’ll give me something and won’t even know it. I’ll never see it, but neither will they. C’est bien ça. They’re coming. Get ready. Take your picture.”

We introduced ourselves and spoke for a few minutes. Perhaps I remembered his name in my journal later that evening, but all that remains of my memory is the portrait he directed me to make. Thirty-five years later the blind man reappeared, wearing the same overcoat and stocking cap, in an elegant monograph by an acclaimed photographer whose focus darted between one of his glass eyes and his hands, begging for the money shot.

If the first photograph depicts exploited tourists, in the second, standing in front of the camera, the subject decides where and how the photographer will stand and frame what will become his self-portrait at work. These anecdotes illustrate lessons learned from a new anthology of projects collected to encourage us to question what and how we are seeing when we view or make photographs. Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography1 proposes what may be the most ambitious pedagogy ever published for the medium. Edited by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler, Collaboration asks and answers, albeit provisionally, “what do we learn when we look at photography through the lens of collaboration. This book is a practical experiment, a theoretical proposition, and a pedagogical tool for approaching that question.” [9]

What is photography? That is the question. Making an “ontological assumption” about the medium, the editors define collaboration as the irreducible “condition of photography in the most basic sense—photography generally requires the labor of more than one person,” especially the work of those “disregarded or unnoticed” after being objectified in photographs. Dividing the medium into “eight kinds of collaboration,” Collaboration is organized in overlapping clusters, each one subdivided into squares of information, like a smart whiteboard. This format, illustrated by a full-page [8] grid of snapshots depicting lectures and zoom calls, is reminiscent of workshops, seminars, and exhibitions where the book germinated for over a decade at elite universities.2 Each square encloses a project producing images of and texts by persons both in front of and behind the camera, accompanied by commentary from contributors who the editors “believed would have a thoughtful reaction” [13] to the work. To reinforce the book’s function as a pedagogy within an academic bureaucracy, the editors institutionalize themselves and their research by calling their team CoLab. They give each project a CoLab title and provide a “technical vocabulary” of these terms. Editors contribute to or have work featured in individual projects; CoLab signs their contributions as an editorial collective.

Cluster titles provide guideposts to the pedagogy of projects that awaits us. Some, like “The Photographed Person Was Always There,” “Reshaping The Authorial Position,” “When A Community Is At Stake,” and “Co-Archiving” seem self-explanatory. Another offers conventional wisdom: “Photography Preserves Sovereign History As Incomplete.” Still others employ a language of privileged discomfort prodded by neologistic allusions: “Iconization Is Preceded By Collaboration,” “Potentializing Violence,” and “Sovereign And Civil Power Of The Apparatus.” These broad themes of subjectivity, authorship, inclusion, fetishization, intimidation, power, and violence underpin Collaboration’s global projects documenting human behavior from joyful to so horrific that some contributors are compelled to exercise poetic license in order to avoid the brutality of the photographic evidence.

With introductory [NOTES] TOWARD A MANIFESTO, an ambiguous title in all caps that eschews labels, the editors begin with “a set of propositions about the hope and the harm” photography has throughout its history “imprinted on different forms of social life: individual and collective.” The paragraph below encompasses many of these propositions:

“Although photography was institutionalized as a technology of imperial, patriarchal, and racial power, since many have always been involved in it—as conscripts or volunteers—it is irreducible to these ideologies, institutions, and structures of power. The lens of collaboration enables more than just a way to look at and view images that sometimes were taken against the will or without the consent of others. Often the presence of these non-consenters is traceable, including through the way that they, or others after them, sought to limit the power that was exercised against them, even if just by pointing to it as being part of a certain abomination, excess of power, and coercive ideology. Collaboration is also an attempt to think about the participation of the many, under various conditions, in the event of photography, and to undo the structures of viewing photography as if the many who impacted the event of photography in different ways were not there. They were always there.” [9]

However horrifying the medium’s history, photography must not be reduced to its worst exercises of “imperial, patriarchal, and racial power,” thus Collaboration’s projects celebrate community as well as analyze “a certain abomination, excess of power, and coercive ideology.” Everyone in and out of frame collaborates together for “photographic events as they unfold over time,” [11] including the viewer. Those in front of the camera the editors call “photographed persons … as a suggestive and respectful correction to the habit of objectification.” [13] Because objectification is not objective, this outspoken promotion of respect, a potentially obsequious approach, over impartiality, the scientific method’s impassive directive, highlights how language records what we understand and misunderstand in photographs of and by “conscripts or volunteers.” Militaristic metaphors emphasize the willful or unwilling collaboration in service of imperialist cameras by photographed persons, as well as everyone and everything else before, during, and after in-camera exposures.

Sympathetic to the editors’ proposed pedagogy, many contributors weave ideas of collaboration into their texts using analogies, commonplaces, metaphors mixed and unmixed, oxymorons, similes, and other literary devices that chart the expanse of the concept when pulled out of context:

“Successful collaborations, like successful lovemaking, cannot be forced by one person onto another.” [24/25] “There is no contradiction here between photography as individual art and a collaborative practice involving the photographer as conductor of multiple authors.” [32/33] “Few bodies of work offer better examples of the act of collaboration as both coerced and emphatically denied than this corpus of mug shots taken in the context of contesting civil rights.” [38/39] “the grammar, meaning, and uses of photography: the reciprocal relationship between the maker and the subject; collaboration as a means to subvert authorial identity….” [46/47] “What kind of collaboration is sex and what kind of sex is posing for your lover?” [72/23] “collaboration is one of those nouns that manages to encompass opposing meanings, referring at once to positive cooperation among people and traitorous collusion with an occupying enemy.” [176/177] “All photography contains, hides, and discloses social relations.” [244/245] “Collaboration emerges somewhere between the accidental and the intentional.” [88/89] “This exercise in collaborative meaning-making, stretching across space and time, is the richest collaboration of all, and also the most fraught.” [134/135] “Perhaps the best collaborative practice is to withdraw oneself from the burdened duty of interlocutor … Perhaps the most effective gesture is to not initiate or take the photograph at all.” [70/71]

While it may be better to say nothing and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt, semantic solidarity comes with unintended consequences. Literary devices configure the medium to perform as a player on the stage, equal, if not superior, to the other players in a larger “event of photography.” This event the editors present as part freeze-frame, part historical continuum, part collective unconscious, “mediated and prolonged through later encounters with photographs.”3 [12] Polymorphous ideologies endow cameras and pictures with powers of independent thought and action. Events of photography, to be distinguished from the photographic acts that sponsor them, add to the editors’ expanding definition of the medium as an impersonal, malleable, omniscient, and universal apparatus “that involves a more or less contingent group of participants, including photographed persons, laboratory workers, translators, distributors, colonial archives, and museum curators, as well as the state and the market.” [227]

And the kitchen sink. What Roland Barthes infamously called a photograph’s “tireless repetition of contingency” catalyzes a fundamental uncertainty principle in any event of photography. How to frame the unforeseen? Although diversified like their projects by cultural differences in historical space and time, several contributors structure their commentaries with a universalizing rhetoric that whispers a bothsidesism typical of mass media attempts to manipulate public reactions to egregious events. One of the two sides will be photography itself, a self-actualizing automaton. With anthropomorphism, universal metaphors genuflect discursively, but before what belief systems? Answers we will seek in fragments torn from selected texts contributed to some of Collaboration’s most profound projects.

David Campany [62/63] takes a leap of faith in his commentary about an emotional project documenting the friendship shared by photographer Julian Germain and Charles Snelling, an elderly widower who for several years accepted Germain’s desire to take his picture as a “natural thing” to do. After his friend’s death, as he worked through his grief in his archive searching for what would become exhibitions and a monograph, Germain found himself deeply affected by his memories of Charlie. “This influence,” Campany opines, “might be understood as the effect of an unconscious form of collaboration,” a reasonable assumption, given that Germain’s photographs are both enactments of their collaborative friendship, and an homage to his friend, symbolized by his adoption of Charlie’s family album design and vintage snapshot color palette. “Some of the photographs seem to have resulted from an exceptionally strong exchange between the two of them, but others less so.” With collaboration as an aesthetic measurement for visual strength, he concludes that we “cannot always tell from photographs exactly what the relationship was between photographer and subject,” and supplants, in a jump from science to poetics, exactitude with anthropomorphism. “For all that they show,” Campany insists, “photographs do not explain themselves or account very clearly for their own making. They leave gaps and cover their traces.” The critic does not explain how inanimate objects justify or dissimulate their existence. Maybe it’s a pun, a play on a photograph’s indexicality. “In the end, however,” Campany cleverly contradicts himself, “the viewer is a third collaborator, witting or unwitting. It is the viewer who makes the interpretation and shapes the meaning, and is in turn affected.”

What triggers this affectation? Where is the frontier separating history from literature; or have these two modes of thinking and writing become interchangeable? How do literary devices create meaning in historical discourse? While anthropomorphic narratives reify what Vilém Flusser recognized as “the world of magic” in the “space and time peculiar to the image,” or what Barthes called “an emanation of past reality: a magic, not an art,” these fantasies exclude, and ultimately negate, human agency.

An excellent example of this negation occurs in Michael Mascuch’s contribution to the project about 16 year-old Khmer Rouge “camera operator” Nhem Ein, who photographed thousands of “cadres” before they were tortured and executed. Mascuch [236//237] imagines a medium with free will: “Photography collaborated in that particular ‘bureaucracy of death.’” No. Human beings weaponized the tool and photographed the victims. The teenager knew his comrades would beat his subjects to death, “but after seeing the same thing every day I got used to it. It became normal…. The cries from the victims were especially loud at night….”

Anthropomorphism allows the unthinkable to inject some notion of collaboration into each event of photography, no matter how depraved. It all takes place somewhere on a non-specific historical continuum. “The identification of a single figure and name, an agent or perhaps an agency such as … the Khmer Rouge,” Mascuch obfuscates, “is part of history’s attempt to apprehend a vast and complex phenomenon involving millions of people over thousands of miles and more than a hundred years: an ongoing moment, for which photography is the ideal medium of perception and projection.” And futility: “Photography renders everything in a fraction of a second and reveals nothing about what is actually taking place.”

Mascuch’s commonplace erases Collaboration’s pedagogical transformation of photographic acts into historical events. CoLab reports that “the US was involved in facilitating the emergence” of the Khmer Rouge, thereby implicating it in the Cambodian genocide. Next to the rows of identity pictures exhibited at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the scholar anthropomorphizes again. After initiating the genocidal process, photography provides evidence for the post-genocide reconciliation. “Photography is collaborating in the fresh impressions now appearing here” to offer “a shimmer of possibility of justice” in the courts, without mentioning the anonymous workers who performed the painful “scrutiny of evidence relating to the S-21 murders….”

To create evidence for subsequent scrutiny, Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who discovered multiple sclerosis, among other diseases, incorporated photography into his diagnoses of hysteria, a disease whose pathology has been traced to superstitions first documented thousands of years ago. Ulrich Baer [78/79] discovers a multi-sensory “something that has haunted photography from its inception to this day: the medium’s suppression of sound and speech.” Pictures may be worth a thousand words but they can’t talk. With this absurd anthropomorphism, Baer awakens Charcot’s female patients to hundreds of years of sexist ignorance. “Women diagnosed as ‘hysterics’ (who earlier would have been branded as witches, heretics, or false prophets and excommunicated, ostracized, or burned at the stake) protest their silencing by a male-dominated culture, by medicine, by photography—through speaking with their bodies.”

That is to say, through performing for the gallery. To “protest their silencing” Baer refers to a series of photographs depicting Augustine, Charcot’s patient Louise Augustine Gleizes, who as a child had been molested then raped, began to suffer from post-traumatic hallucinations and violent seizures, and spent her adolescent years incarcerated at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital. Under hypnosis by Charcot, she exhibited “hysterical” symptoms for an audience of doctors, students, visiting dignitaries, journalists, artists, and photographers. Even Freud was in attendance. “These photographs,” Baer continues his anthropomorphic analysis that uncovers a mild castration complex with photography wielding the blade, “do not invest us with the authority to draw a sharp line between trauma and theater, physiology and performance, which repeats mainstream gender divisions that place female subjects on the side of play-acting and male subjects on the side of truth.”

Not necessarily. As an active collaborator in the documentation of her symptoms, whether or not under hypnosis, Augustine was able to hold her poses long enough for photographers to produce beautifully detailed portraits. She became, in the words of historian Asti Hustvedt, “the ‘supermodel’ of the clinic, the hysteric whose picture was taken again and again” and whose charisma in collaboration “with the photographer’s careful composition and contrasts between light and dark, make her images more artistic … and offer an idealized illusion of hysteria or an idealized illusion of pretty much anything the spectator might wish to project onto the picture.”

Eventually Augustine refused to pose. In 1880, nineteen years old and five years into her incarceration, she dressed as man, left the hospital, and disappeared.4 Over time, doctors stopped diagnosing hysteria and the term became purely descriptive. A century will pass before the American Psychiatric Association removes hysteria from their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

We will need to read history as literature without science in order to understand Baer’s staking “Freud’s claim to epistemological supremacy” as well as the “‘hysterical yawning,’ which so unsettled Charcot and Freud that they questioned some of the assumptions of the very system of patriarchy that bestowed on them authority as scientists.” In their moments of self-doubt, did these patriarchs wonder what was real and what was rhetoric as they watched their patients perform for the camera? Or were they, like Baer, not invested enough to decide what is truth and what is play-acting? To calm any confusion, the scholar slings an interdisciplinary metaphor: “Instead, these images ask us to bear witness to the gaping silence that they make startlingly visible.” Silence is still deafening but no longer invisible. What he calls the “chauvinist celebration of these images as ‘the poetic event of the 19th century’ by surrealists Louis Aragon and André Breton” Baer will oppose in his conclusion. Henceforth we will comprehend photographs of Charcot’s patients not only “as documents of oppression and coercion but also as acts of resistance that unsettle a conception of photography that splits the world into those who are shot and those who hold the power to assign them meaning.”

While the chiaroscuro of Augustine’s attitudes passionnelles reflects Renaissance aesthetics, her portraits were designed for precise visual dissection. “All this part of the seizure is very fine, if I may so express myself,” Charcot wrote, “and every one of these details deserves to be fixed by the process of instantaneous photography.” To accomplish this photographic feat, one of his photographers, Albert Londe, fashioned a camera with nine lenses whose shutters were triggered by metronome then tripped with jolts of electromagnetic energy. This took place in a “state-of-the-art studio at the Salpêtrière, where props such as gongs could be used to freeze a hypnotized hysteric in easily photographed poses, and a camera he invented could document an entire hysterical attack in a series of chronophotographs.”

How did chauvinistic surrealists sublimate their onanist enthusiasm for Charcot’s sci-fi theatre of hysterics, whom they perceived as women in hypersexual abandon? In 1928 they reprinted pictures of Augustine in La Révolution Surréaliste magazine’s celebration of “hysteria’s fiftieth birthday.” No longer medically relevant, hysteria was recycled into a poetic catalyst.

Is it more or less respectful to Charcot’s patients to study their portraits for their participation in a century’s visual, social, political, and aesthetic cultures, than to believe, with Baer, that photographs transcend exploitation by revealing the intentions of photographed persons resisting their oppressive condition? Collaboration becomes an act of omniscient faith; we bring them to life beyond their likeness. “In the last analysis,” Charcot wrote, “we see only what we are ready to see, what we have been taught to see. We eliminate and ignore everything that is not part of our prejudices.” Perhaps this is why CoLab thinks his pictures seem to have been “taken as if the photographed persons were not there, only their symptoms. This is part of what makes them painful to look at.” Subjected to what Michel Foucault defined as the “medical gaze,” our discomfort sublimates semi-unconscious tensions between our unwilling suspension of disbelief, that is to say, our imposed belief in the camera’s objectivity, and our instinctive distrust of its mechanical inhumanity.

If ambivalence is the medium’s original sin, anthropomorphism is its serpent. “Photography,” proposes curator Audrey Sands [34/35] introducing Rineke Dijkstra’s beautiful, long term portraiture project with a young refugee, “can be thought of as stealing one’s image, even a theft of the soul.” Lord have mercy! Whatever the definitive source of this anthropomorphic cliché, it assumes photography’s innate will to violence and is typically attributed to superstitions believed by indigenous and colonized peoples,5 and by Barthes, who thought he encountered zombies, “that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead.” Subjecting superstition to a positive spin on photography, Sands asks, “But what happens when photographing is an act of giving back? When being photographed is affirming rather than negating life?” Of the numerous sources feeding this reductio ad absurdum, the most melodramatic is Barthes’s assumption that “All those young photographers who are at work in the world, determined upon the capture of actuality, do not know that they are agents of Death.” To this nihilistic rule, Sands proposes Dijkstra’s portraits as exceptions.

Recalling what Barthes called his “‘ontological desire’” to determine photography’s “essential feature … distinguished from the community of images,” curator Julia Byran-Wilson [150/151] asks “What makes a photograph a photograph?” Blending ontology with anthropomorphism, she praises artist Alfredo Jaar’s 1996 project, named after Barthes’s Camera Lucida, a primary text for graduate students in disciplines from photography and art history to anthropology and comparative literature. The artist “distributed one thousand cameras” in one of Venezuela’s poorest urban areas to curate an exhibition for a new museum unwanted by the inhabitants, Jarr wrote, “to offer to the community the opportunity to conquer this space, to make theirs the walls of this institution that was imposed on them.” The curator anthropomorphizes how the public, including “so-called amateurs … both embraces and rebels against the presumed freedoms of photography.” It is photography’s presumption of freedom to take pictures, and not that of the people to whom Jaar gave the cameras with an invitation to photograph their lives “in complete freedom.” Rather than questions about what this fleeting liberty signified for the artist’s conquering snapshooters, this anthropomorphism uncovers a poetics stretched between aphorism and platitude for a Photography with a capital P that Byran-Wilson insists “always exists in relation to, and exceeds, Barthes’s ‘community of images.’ It is also undone by that relationship.”

One way out of this done, overdone, and undone conundrum of non-specificity is a life-affirming sidestep around this Barthesian pitfall. “The camera,” Collaboration’s editors confirm near the end of their manifesto, “is not a demiurgic tool that generates death and resurrects bygone moments captured in photographs, as some theories of photography have considered.” [12] This diplomatic avoidance of the past fifty years of repressive tropes in photography history, criticism, and education remains unheard by Barthes’s acolytes, who contextualize the semiologist’s phenomenological ideas despite their lack of relevance to specific projects or to Collaboration’s overall pedagogy.

In 2002, colonialism’s foremost chronicle announced the discovery in “a remote Afghan village” of the woman whose 1985 National Geographic cover portrait seduced picture editors everywhere with a bright green-eyed tween girl in a refugee camp. According to curator Mary Panzer, [90/91] the image of a nameless “young, female, in distress,” would “come to represent innocents in need, children, refugees, victims of natural disasters, and remote conflicts.” The child’s old soul gaze would inspire first world market empathy in the service of which the photojournalist first took her picture. Eventually the photograph transcended the photographer as its worldwide distribution made him almost as famous as her likeness; internet search engines still return the Afghan girl’s magazine cover when prompted with the photographer’s name. Celebrity required her rediscovery. Like a colonial hunter on safari,6 the photographer, “who first captured her image, tracked her down in the mountains of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.”

“Found” screams the title in a blood red typeface. So she was. The “National Geographic used then-advanced [sic] iris recognition software to establish her identity.” During an examination that looks almost as unpleasant as reading about it, an ophthalmologist examined the woman’s eyes to “check that her iris patterns and eye freckles matches those” of the girl on the old magazine cover. Her identity established, she and her family were molded into public figures to be exploited “in publicity about the millions of Afghan refugees who remained stateless,” inspiring “another global round of publicity, including a television special and a second National Geographic cover, for which she wore a burqa.” Before outing her in the article and with a brilliant stroke of commercial hypocrisy, the magazine preserved her anonymity on its cover while having her hold her celebrated portrait. “I was a child,” she said years later. “I didn’t like photos. In Afghan culture, women don’t appear in photos. But there wasn’t much choice.” Collaboration prints her name and includes before-and-after pictures, even though, as the magazine reported in 2017, “the attention she's gotten since being identified as the subject of National Geographic's cover puts her at risk from conservative Afghans who don't believe women should appear in the media.” After the return of the Taliban, Panzer concludes, she was resettled “in Italy” where “no one knows she was once the Afghan girl. ‘And that’s fine with me,’ she said.”

Thus a person unwillingly photographed, Panzer clarifies, “embodies the definition of an icon, an image that travels independently of its original subject and acquires a life of its own through reproduction and appropriation.” What began as the photographic exploitation of an anonymous child became a mission to identify and save the adult from the poverty and culture she grew up in, whose representation continues to feed the photographer’s ego if not his bank account. Whether or not her transplantation to the West assuages the mass media industry’s collective guilt, the story of her astonishing life cannot be told without hearing the oft-praised photojournalist’s heroic self-promotion, like his boast for having cinematically saved the image “from the cutting room floor” so his portrait could become “one of the most famous photos in history.” A masterclass in hubris, this panegyric for an exploiter is more newsworthy than an exploited woman’s privacy. As an unwitting ambassador for neoliberal post-colonialism, this project propagates the very “imperial, patriarchal, and racial power” that Collaboration seeks to undermine.

If Collaboration’s vanity press treatment for National Geographic’s most notorious exploitation seems unusual for a potential history of photography, it accentuates a sense of cognitive dissonance felt when its editors and contributors wear their hearts on their sleeves:

For her project The Hotel, photographer Sophie Calle took a job as a chambermaid in order to examine “the personal belongings of the hotel guests.” Leslie Hewitt [50/51] aestheticizes Calle’s obsessive invasion of her anonymous subjects’ privacy by redefining voyeurism. The photographer’s “fantasies of interpretation” will be found in her “insistence on loosening the privileged gaze and rendering visible that which is intended to be invisible, that which temporarily creates a rupture of the status quo” at the expense of her subjects. It’s ok to say the whole thing sounds pretty creepy.

The editors sound like Tiger Beat breathlessly celebrating the collaboration between Che Guevara and his photographer Korda, [82/23] “who together produced an image of a young dreamy revolutionary figure that circulated in different colonized places or among oppressed groups in the West … That dream died in 1967 when US-trained Bolivian soldiers assassinated him.” Such hero worship neither historicizes Che, nor wonders how Korda’s portrait became symbolic, not of the dashing Stalinist with bedroom eyes, but of his transformation from Guerrillero Heroico into radical chic for sale everywhere to wannabe rebels without a cause. As Paloma Duong notes in her perceptive contribution to the project, “ubiquity desensitizes and dilutes.”

Cindy Sherman, gushes Tavia Nyong’o, [252/253] “has decisively shaped the history of art photography since the 1970s by demanding we look again at the dynamic between photographer and sitter.” Although Sherman’s prints are marketed to an exclusive public, Nyong’o does not consider the position of the artist in an aristocracy defined by extreme wealth. Rather than recognize the historic role of court jester, the scholar praises Sherman for teaching “that reclaiming the apparatus allows one to perform both for and against the camera”; in other words, for evading, anthropomorphically, the camera’s “controlling gaze by seducing it, exposing the camera to itself and placing it firmly within a space of shared control and accountability.”

Yet it is not the camera which (or should we say who) is responsible for “Self-Possessed,” a series of portraits and theatrical tableaux depicting various historical, contemporary, and fictional characters, created by artist Jessie Mann collaborating with Len Prince, a successful celebrity photographer. Mann, who began modeling as a child for her famous mother, was a college student when she met first Prince, whose practice was “attuned,” according to historian Sarah Parsons, [94/95] “to the demands of his corporate clients and powerful subjects.” Mann recalled, “I blurted out this bundle of ideas about the subject as an active agent in art…and Len said ‘I need a muse’ … Only once we had made our first image together as collaborators, I realized what a powerful thing it was—to muse.”

Not powerful enough, apparently, for the photographer to listen to his muse, whose research Prince damned with faint praise: “Jessie would arrive to our sessions with a small library of knowledge which she’d want to generously share with me, which I refused to ensure our collaboration to be entirely authentic.” Does spontaneity determine authenticity, or is Prince’s refusal merely a maneuver to control the final product? “For all the project reveals about the potentialities of collaboration,” Parsons misses the irony of the series title and rationalizes the model’s exploitation: “it also exposes how those potentialities are limited by the structures of the art market and art history. Because Prince shouldered the material costs of production, the pair had agreed that he would receive any profits from sales. As a result, commercial galleries offered prints … with the authorship and legal copyright assigned only to Prince.”

Was there a contract between photographer and muse? If so, after hours of “extensive research” and “collaborative work during long, elaborate shooting sessions,” did Mann happily sign away her intellectual property with her likeness? What does it say about the photographer’s professionalism that he would willingly enter into an agreement allowing him to profit from his muse’s youthful naïveté? Just business as usual. That Mann is the intellectual force behind the project is not in doubt. “Throughout our project,” Mann told Aperture in 2006, “the sense of the protean character has been coupled with an examination of what it is to be in front of the camera, as well as to be conceived of by the audience. When applied specifically to my experience and existence, the photographs become experiments in the metaphysics of identity.” Or, as innovative scholar and photographer Gisèle Freund wrote in her autobiography, “it is the model that counts, and the role of a good photographer is to be the sensitive instrument by means of which a personality is revealed.” Authorship can be shared, independent of any financial arrangements. It is Mann’s sense of the uncanny that breathes life into Prince’s technically flawless pictures, and not the other way around. The copyright should reflect this collaboration.

Is it respectful, or even ethical, to label “non-consenters” in photographs as collaborators in their own extermination? Of course not. Not even for assimilation into an academic category of photographed persons. Symbolizing Collaboration’s ideological problematics7 is the glossary, a short list of entries like “Cluster Text” and “Contributor Text.” Missing are significant concepts such as event of photography and apparatus, the latter a touchstone for postmodernist philosophy while the former establishes Collaboration’s expansive pedagogies. Given the editors’ wish for us “to work with the book, to use in classrooms, workshops, community centers, and in union meetings and at home, and to add projects that you consider could expand the conversation,” [12] the glossary is an infantilizing overstatement that smacks of privilege, but their hearts are in the right place. In any case, to expand Collaboration for the general public requires dedication to a mission, best described by the Khan Academy, “to provide a free, world-class education to anyone, anywhere.” Such an initiative goes against the capitalist apparatus of the publishing industry.8

Documenting some of the better and the absolute worst aspects of human behavior, Collaboration’s editors and contributors stare down whitewashed histories of photography, bringing into blinding daylight dark horrors that continue to bleed from the past into the future. Transcending their summarization, the events of photography that Collaboration documents defy the anthology’s literary affectations.9 Given the increasingly authoritarian restrictions on public debate, Collaboration’s pedagogies are in danger because they require both an unbiased investigation into the medium’s history, and an ethical embrace of its practice.10

Understanding photography as a tool of oppression is almost as old as the medium itself. By 1871, photographs were already expressions—evidence—of lethal power: after the Paris Communards proudly posed for their portraits on the barricades, the police used the pictures to identify the rebels, many of whom they lined up against the wall and shot. Among the dead, the ratio of misidentified militants to civilians remains unknown to this day. “For the first time in history,” Gisèle Freund wrote a century later, “photography became an informer for the police.” And Susan Sontag elaborated authoritatively, defining what evolved into a canonical subconscious understanding of photography that Collaboration would shake awake from its numbing slumber: “there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as the camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder—a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.” Fearful tears dissimulate the deadening of the “social conscience of liberal sensibility” that photographs were supposed to represent for the bourgeoisie. “Documentary testifies, finally,” deadpanned Martha Rosler in 1981, “to the bravery or (dare we name it?) the manipulativeness and savvy of the photographer, who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay, or combinations of these and saved us the trouble.” Forty long, stultifying years after Sontag, Ariella Azoulay will criticize postmodern theorists “who bore witness to a glut of images [and] were the first to fall prey to a kind of ‘image fatigue’; they simply stopped looking. The world filled up with images of horrors, and they loudly proclaimed that viewers’ eyes had grown unseeing, proceeding to unburden themselves of the responsibility to hold onto the elementary gesture of looking at what is presented to one’s gaze.”

Buttressing this unburdening is a denial of, or a wishful thinking attempt to refute, photography’s truth-value. However we may choose to understand what comedians call truthiness, to emphasize Paul Valéry celebrating the medium’s centenary in 1939, photography teaches us not to see nonexistent things that we used to see so clearly. These days it’s harder to keep the faith with what’s right in front of us. "Degradation of taste, color, composition, character, expression, and drawing,” Denis Diderot discovered in 1765, “have kept pace with moral depravity." Centuries later, it is still “impossible to see the world anew,” as Susie Linfield so wisely understated, “for we are all helpless, brainwashed spiders caught in capitalism’s ideological web,” intellectually neutered, poetically challenged, and politically disassociated as our taxes fund oligarchs at home and genocide overseas.

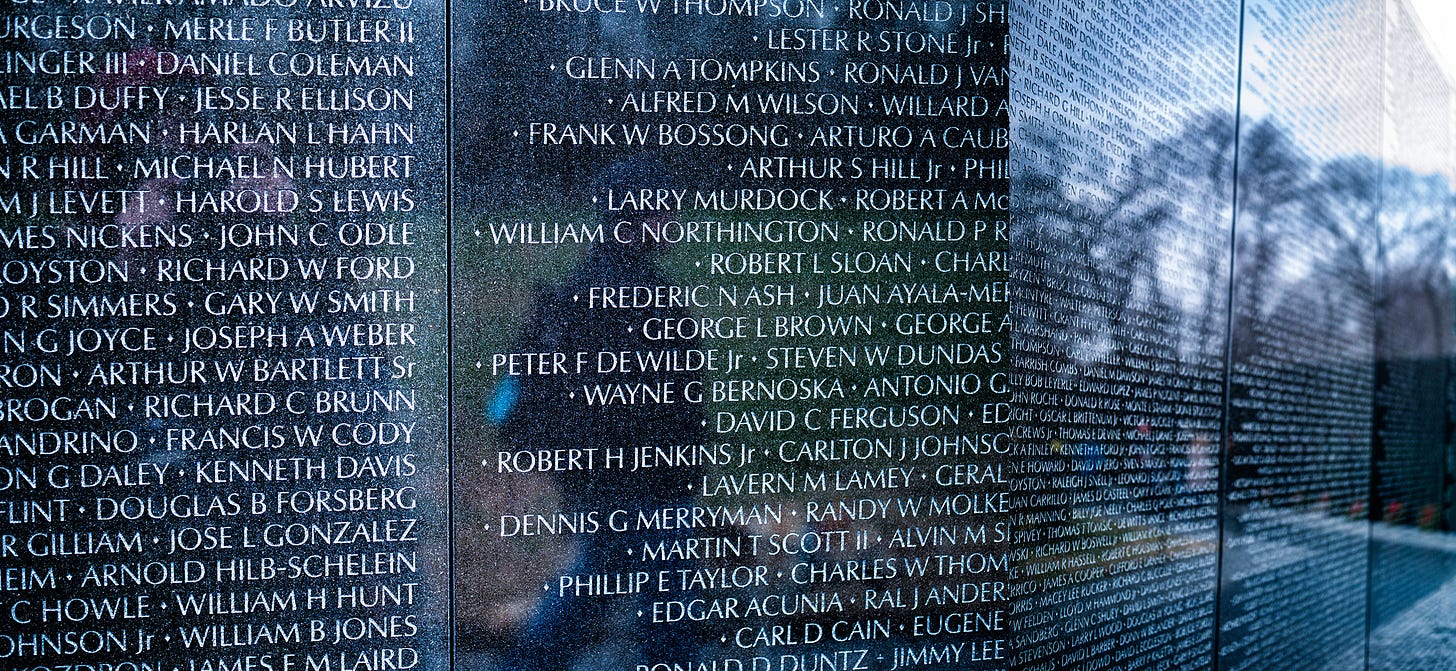

An unknown number of the 58,281 names on the Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C. belongs to people who did not want to be there. When I was twelve I wanted to be a combat photographer. Four years later I was terrified I’d be drafted and sent to Vietnam. On television I watched body bags loaded onto helicopters split-screened with police and rednecks beating hippie antiwar protesters. My sister’s boyfriend wrote me, just before his tour of duty ended, and told me how he put himself through heroin withdrawal because he knew he could never afford, or even find, such high quality horse at home. On the 2nd of February the Selective Service held its annual lottery to determine the military’s conscription for the following year. My birth date was in the low 200s. A high school friend’s was number 3. He was in a panic but neither of us was called up. The war was winding down, too late for the people populating the polished black granite.

Fifty years later, I stood before them stupefied, misunderstanding why these thousands of souls, unknown to me and sacrificed to a domino theory of geopolitical warfare, were able to awaken memories that my lucky number had allowed me to forget. How to photograph the world reflected in this wall without disrespecting those whose deaths are etched in stone. Is a selfie on this sacred surface not a nihilist’s blasphemy? The names of the fallen block my reflection and everything else is a blur.

Collaboration retails for $85 US.

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler, editors. Thames & Hudson, Ltd: 2023. Page numbers in brackets. Selected textual fragments are printed in italics to indicate our emphasis. The author asserts his authorship and copyright for the photographs accompanying this text. © 2025 George McClintock All rights reserved.

Collaboration includes no specific information about those who collaborated for these photographed events.

Concepts like the “event of photography” and “photographed persons” owe their development to the scholarship of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. Still, it was Susan Sontag who, writing some fifty years ago, described photography in prescient language: “A photograph is not just the result of an encounter between an event and a photographer; picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights—to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on.” Sontag’s prescience notwithstanding, her insight brings about “a non-civil orientation” of the photograph, as Azoulay envisions in her study Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, “which positions the gaze as external to the event of photography” and now privileged enough to be alienated from, indeed apathetic about, civic engagement.

Some of this information about Charcot’s patient is highlighted in reviews of a play, Photographs of A, and a movie, Augustine, the latter featuring a fictional affair between the doctor and his patient. Are these sources as historically reliable as Baer’s anthropomorphic flights of fancy? Didi-Huberman mentions Augustine’s escape in his influential Invention of Hysteria, a volume included in the Sources, but only for the project title.

One source of this superstition is a famously rotund French romancier. It was Balzac who, according to Nadar, “resisted the entirely scientific explanation of the Daguerreian mystery” and whose fear of the camera was based on the belief that “every body in nature is composed of a series of specters, in infinitely superimposed layers.” With each new exposure, “there was an evident loss of one of its specters, which is to say, of a portion of its constitutive essence. … This terror of Balzac before the Daguerreotype, was it sincere or simulated? If it was sincere, Balzac had only to gain from his loss, since his abdominal abundances … permitted him to squander his ‘specters’ without counting.” Missing the joke, Didi-Huberman attributes this belief in specters to Nadar and not Balzac, but his footnote reveals secondary sources, Susan Sontag and Rosalind Krauss, who were not known to write humor.

Photographer as hunter is a typical trope. In his contribution about New York subway photographs by Walker Evans and Helen Levitt with James Agee, historian Douglas R. Nickel [232/233] described their “experiment” as a collaborative conquest in which their individual “pictorial results are easy to confuse. The differences largely boiled down to editorial selection from the spoils.” Using a colonialist discourse rife with hunter/gatherer metaphors, Nickels recalls that “their real quarry was not commuters, but unselfconscious expression.” In keeping with Collaboration’s overall pedagogy, Nickel asserts that “What none of them could fully resolve was whether the higher purpose of art justified the random exploitation of fellow humans who never consented to become art.” When does art’s presumably higher purpose justify exploitation?

There are a few howlers. A favorite sounds like undergraduate AI. CoLab notes that after her friend and collaborator Walker Evans died, Helen “Levitt returned to the subway to photograph and eventually published a book of her own, Manhattan Transit (2017),” eight years after she died in 2009. [232/233] Another spells CoLab “Co-Lab” in the glossary. Theoretical semiologists will have a field day with the suppressed hyphen. Still another wonders if being “more or less contingent” is like being a little bit pregnant.

One curator who bucked the system and gave away a pdf of a limited edition photography anthology shall remain nameless. A photography thought leader, a post-photographic artist, gatekeepers for arts organizations, and writers for diverse publications, all wish they had never heard the curator’s name. Why?

Collaboration with an up-and-coming art star who was arrested and charged with “attempted enticement of one minor boy … and possession and distribution of child pornography.” Within days, the disgraced curator was disappeared from social media. Deleted were interviews and articles featuring the felon, erased were essays and exhibition reviews. The publisher purged the sex offender’s titles from its catalog. Rather than be associated with unspeakable crimes, these acts of ex post facto censorship concealed not only their embarrassing collaborations with the depraved curator, but also their contributions to the art historical archive of late 20th and early 21st century LGBTQIA+ BIPOC aesthetics. Fearing trauma to their reputations, they suppressed their own cultural history.

Why all this attention to a few turns of phrase? Lest we minimize anthropomorphism’s rhetorical power, let us not forget how the literary device, which like an alchemist turns money into speech, is central to the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision that has irreparably corrupted electoral politics in the United States.

In retaliation for rocket attacks and armed incursions into Israeli villages where hundreds of civilians were murdered and taken hostage by Hamas terrorists, Israel prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government has been committing genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza and the West Bank. Former US president Joe Biden, an old friend of Netanyahu, spent some $20 billion from US taxpayers for arms and other materiel for Israel’s genocidal warfare. On his social media platform, the current US president posted an AI-fantasy video of a future Trump Gaza resort and casino.

According to the Interim Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (IRDNA) by the United Nations with the European Union and the World Bank, Israeli forces have damaged or destroyed 292,000 homes; 95% of hospitals are now non-functional.

Pretending that Israel is a theocracy and that protests against Israel’s destruction of Palestine are antisemitic, university administrations attempt to avoid bad publicity by expelling students and terminating faculty members who support the protests.