My claim is to live to the full the contradiction of my time, which can make sarcasm the condition of truth. –Roland Barthes

That all systems end with lies, this is not in doubt. –Paul Valéry

“Aristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men,” laughed Bertrand Russell, “although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives’ mouths.” Photography critic A.D. Coleman postmodernized the British philosopher’s joke, noting that Aristotle’s “hermeneutics never required him to test this hypothesis by looking into a human female's mouth and counting.” Actually, in an act of ancient protest, the hoary philosopher’s wives refused to yawn on command and the First Mansplainer has been the butt of philosophy class jokes ever since.

A peculiarly Aristotelian myopia blurs Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes’ kaleidoscopic Reflections on Photography, first published in Paris as La chambre claire / Note sur la photographie. Only nobody is laughing. Why? Ever since its publication in 1981 and by dint of its pedantic style, the translation has become throughout English speaking academia the most solemnly dissected treatise on the medium. Themes of loss and mourning and pain and death belie the infectious joy Barthes exudes as he advances bemused and musing across Camera Lucida,1 one of the semiologist’s most poignant and humorous texts exploring a subject he acknowledges from the start knowing nothing about, phenomenologically speaking.

Overwhelmed “by an ‘ontological’ desire” to discover photography’s essential, majuscular “genius,” [3] all the while proclaiming his “desperate resistance to any reductive system” or analytical methodology, and wondering “why mightn’t there be, somehow, a new science for each object” like a phenomenology just for himself, Barthes employs a solipsistic method of inductive reasoning, appointing himself “as a mediator for all Photography.” [8] As he begins to unearth the medium’s “fundamental feature, the universal without which there would be no Photography,” [9] he first populates his phenomenological universe with zombies, “that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead,” [9] suddenly undead. Categorically contradicting The Treachery of Images, Magritte’s iconic ironic painting, Barthes winks at surrealistic tradition while announcing that the “Photograph … has something tautological about it: a pipe, here, is always and intractably a pipe.” [5] The signified or what it means dominates the signifier or what it might mean, and the referent or what it is rules over all. “It’s as if the Photograph always carries its referent with itself,” Barthes reminds us, “both affected by the same amorous or funereal immobility … like those pairs of fish (sharks, I think … ) which navigate in convey, as though united by an external coitus.” [6] Smoking a pipe for sex and death while swimming with sharks: that’s Photography with a capital P. A few pages later, Barthes begets his own referent. As a celebrity, he comprehends that “it is metaphorically that I derive my existence from the photographer.” [11] What he wants “to have captured is a delicate moral texture and not a mimicry” nor a simulacrum of his essence, but the best he can hope for is to play La Joconde, deciding like da Vinci “to ‘let drift’ over my lips and in my eyes a faint smile which I mean to be ‘indefinable.’” [11] As he approaches Camera Lucida’s denouement, Barthes discovers in “this kind of question that Photography raises for me … probably the true metaphysics” [85] of complicated answers to simple questions such as “why is it that I am alive here and now?” [84] As opposed to there and then, where and when, Barthes concedes in italics, “realists, of whom I am one do not take the photograph for a ‘copy’ of reality, but for an emanation of past reality: a magic, not an art.” [88] Not a signified, but a signifier. Beyond its alchemically mimetic “evidential force” and from “a phenomenological viewpoint, in the Photograph, the power of authentication exceeds the power of representation.” [89] Ars Poetica has evolved into a new Ars Photographica: like a poem or a person, a photograph should not mean but be, even if photographers, once imagined by Mac Orlan as a knife wielding “headless silhouette who holds the murder weapon in his hand,” are reimagined by Barthes, some fifty years later and somewhat prosaically, as “agents of Death” [92] as well as life.

Counting on his “own notoriety” [63] and not unlike Godard’s Parvulesco, the semiotician’s greatest ambition is to become immortal before dying. After death the resurrection. To commemorate the fortieth anniversary of Camera Lucida’s publication, artist, scholar, and writer Odette England curated an exhibition and a book entitled Keeper of the Hearth / Picturing Roland Barthes’ Unseen Photograph, inviting, as she explains in her preface, “photography-centric artists, writers, curators, and historians” as well as academics to participate in the project. Regarding “one of the most famous unseen photographs in the world,” England instructed her colleagues, “the main criteria for the photograph you contribute is that it echoes, suggests, or reflects Roland Barthes’ Winter Garden photograph,” a snapshot of five year-old Henriette, Barthes’ mother in childhood and the key to his autobiographical roman à clef. This mythic portrait, she told Roula Seikaly, “was also a meaningful entry point for Keeper of the Hearth because as far as we know, no one has seen it or can verify its existence. As photographers,” England continued, affirming an optimistically humanist aesthetic approximating social activism with analytical rigor, “we so often try to make visible the invisible, to give voice to the voiceless, to illuminate hidden or disguised concepts.”

Let there be salubrious sight for the sightless. Like Camera Lucida, Keeper of the Hearth is a nostalgic call and response to, as Charlotte Cotton eulogizes in her foreword, “the enduring capacity of Barthes’ writing to be a creative springboard” for his readers. The pool is deep and wide. “And yet,” art historian Douglas Nickel frets in the book’s first essay, “despite the industry that has grown out of it, and for all the attention it has received, Barthes’ book remains the most misread text in the literature of photography.” Like bumbling undergraduates, we “misapprehend” Barthes’ text because we “are not prepared to read it properly.” How did Camera Lucida, “a deliberately unruly meditation on loss … come to be confused with critical theory”? Good question, even if the term “critical theory” lacks ideological specificity. Has an equally naughty befuddlement blurring intellectual sycophancy with neoliberal capitalism domesticated photography, both in theory and in practice? Yes, Nickel confirms, this domestication “has contributed to the exact worry expressed in the book’s last pages: that photography will find itself tamed, that our responses to it will be rationalized and our approaches formalized into an orthodoxy worthy of citation and entrenched academic protocols.” Ouch! No more footnotes. Handing down his indictment of erudite mediocrity in a collective panegyric for Photography’s great sage, and in keeping with his passive voice, Nickel’s mention of misreading Camera Lucida smacks of ironizing self-flagellation, academia’s always already ubiquitous exercise for the faithful.

Because Keeper of the Hearth is a birthday party, most participants left their hair shirts hanging in the closet. They contributed “a photograph they’ve made specially,” England reports, or they chose an “image from their archive … a personal snapshot, or a found image or object.” No doubt as a favor to the contributors, the book anonymizes their visual contributions. While texts are identified with their authors, images are “unobscured by the credits,” untitled, undated, unidentified by artist, and often un-page numbered, until an unnumbered page in the back alphabetically lists the artists by family name and number. Who photographed the pit bull terrier, [1] rendered as a defective negative from a vintage Polaroid? First we have to figure out the page number, then scan the list until we find a name next to the number. Even when we learn the artist’s identity, what’s in a name? There is no way to ascertain if, how, whether, and when the artist created or found the picture. Does it matter? Is it need-to-know? “Though text about artworks can be prescriptive,” England suggested in her doctoral thesis, “a lack of writing places emphasis on the visuals, which bestows inference.” What are we to infer? With no additional information forthcoming, this unforced vernacularity accentuates the ambivalence symbolized by opening a photographic celebration of Barthes with a picture of an attack dog, albeit one neutered of its referential thrust such that it “feels like a faint palimpsest.” It is language which speaks, not the author, wrote Barthes in his famous Death of the Author. The suppression of origin, title, date, etc. confounds our notion of authorship; Keeper of the Hearth refracts, semi-unconsciously perhaps, what critic Geoff Dyer humorously called Barthes’ “claims to author-ity,” not by killing its authors, but by forcing us to dig them up. And we still don’t know if, how, or why the pit bull suggests, reflects, or echoes Barthes and his picture of little Henriette.

Not to worry. We’re not supposed to know. Ignorance is punctum. “(I cannot reproduce the Winter Garden Photograph,” Barthes announces parenthetically. “It exists only for me.” For us, Henriette the faded sepia snapshot “would be nothing but an indifferent picture, one of the thousand manifestations of the ‘ordinary’ …. at most it would interest your studium … but in it, for you, no wound.)” [73] With us Barthes has no reason to share yet another example of studium, his neologism for a “rational intermediary of an ethical and political culture” invested with his “sovereign consciousness,” to wit, the vernacular. Nor are we sensitive enough to feel his punctum, “this wound, this prick,” to read “this mark made by a pointed instrument,” [26] to play his Mallarméan “cast of the dice” [27] that will never abolish chance. Barthes neologizes punctum as “a kind of subtle beyond — as if the image launched desire beyond what it permits us to see: not only toward the ‘rest’ of the nakedness, not only toward the fantasy of a praxis, but toward the absolute excellence of a being, body and soul together.” [59] Is Barthes talking about his mother? No, but he feels the same ejaculating punctum that “shoots out of” his Winter Garden picture “like an arrow, and pierces me” [26] from Henriette’s “figure of a sovereign innocence” [69] as he does from an “erotic photograph.” [41] Not for nothing Philip Prodger, aware of his own “epistemological shortcomings,” imagines Barthes fetishizing his mother’s likeness like a porn star’s with “the only picture to capture his mother’s true essence. He wrapped it then in brown paper and slipped it into his jacket pocket, close to his breast. Sitting in his study he sees the package with fresh eyes, the enclosure folded lovingly, its surface worn smooth and glossy from being carried against his chest. Now he eases the photograph out of its wrapping … He weighs the image in his mind, touching the ballpoint of his pen absently to his tongue, and writes some more.” Barthes, whose “lips curl ever so slightly into a smile,” embodies Mona Lisa once again. And not a moment too soon; it’s taken forty years for Barthes’ oedipally structuralist punctum/studium dichotomy to deconstruct like a rhetorically immaculate conception into scholarly fantasies written with ancient metaphors.

Punctum or no punctum, most participants do not follow Barthes’ example in Keeper of the Hearth. No things but in ideas. Many images synthesize popular tropes of self-referentiality with an aesthetics of visual anonymity symbolized by partial visibility, as if to embody Barthes’ oft-repeated obscurantist dictum that “a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see.” [6] First we have to see what we see and don’t see, like Rumsfeld’s known and unknown unknowns. Easier done then said. Vernacularity and pseudo-vernacularity function as conceptual sleight of hand; a photograph identifies itself first as a photograph, preferably fading, musty, or torn, just in case we don’t know what it is we’re looking at. Then, in a bluster of black and white indistinguishability, truck tracks lead right out of a snowplowed parking lot into blinding lens flare. [2] In a pallid magenta landscape monstrous arboresque shapes loom behind a blurry bank of distant fog. [14] A flared-out mushroom cap sits atop a bulbous, phallic stalk in a discolored Impossible Polaroid SX-70 shot. [27] Faded light leaks flash across a snapshot depicting somebody’s grandchild on a tricycle in a Miracle on 34th Street neighborhood. [30] Showing us the back of the substrate, a face down Fujiroid positive reveals an indentation or trace of a figure au recto, as if drawn with a stylus. [99] Can’t go anywhere in the USA without seeing a gun; in a partially solarized negative, an elderly woman grimaces violently as she aims a target pistol. [253] A toddler stands partially out of frame next to a grandfather figure kneeling beside her; the faded color snapshot’s preciously off-center composition exposes the lack of parallax correction produced by Brownies and Instamatics when placed too close to the subject in a wonderful demonstration of involuntary cultural aesthetics because, as we all know, people do not see things askew, cheap cameras do. [114] Superimposed over snow-covered evergreens next to a ski chalet is a New York slice. Bon appétit! [237] A young woman dressed like Madame Alexander sits patiently, all her highlights, midtones, and shadows blown away in an extremely overexposed picture covered in chemical stains. Lest explosive overexposure is not metaphorical enough, the image is spread over two pages [100/103] divided by a third, lighter weight and slightly smaller page [101/102] from the paper stock used primarily for text, thus making it impossible to see the picture unencumbered. With a similar maneuver, the design impedes our view of a rural garden in which a woman wearing a sleeveless blue and white house dress raises both her arms, like a bird about to take flight. [126] We know it’s a bird because, in the upper right hand corner of the inserted facing page, a crow spreads its wings in black and white. [127] The layout interferes with our visual experience of the portrait in order to impose another more obvious and less visceral simile. Turn the page to see a raptor zeroing in on us from above the other side of the encumbered garden. [129] Thus Keeper of the Hearth reinforces contemporary art photography’s self-referential dogma: we know we’re looking at pictures because we cannot see them unobstructed, literally or figuratively.

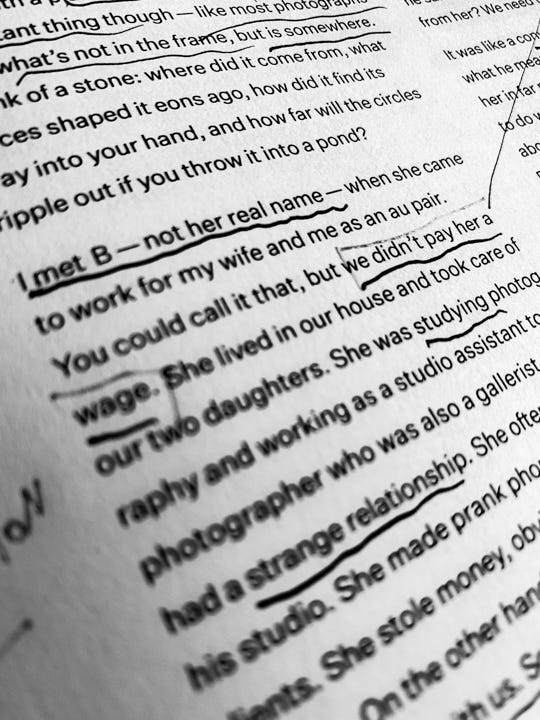

Be inspired by a picture that Barthes obscures between the lines, create something or visualize its idea, then overshare it like unsolicited advice or an unwanted confession. Such is critic Lyle Rexer’s modus operandi for his contribution to Keeper of the Hearth. “Like most photographs, you can see….” Beginning syntactically challenged, Rexer anthropomorphizes photography—we are all photographs now—before maladroitly paraphrasing Barthes: “The important thing though—like most photographs—it’s what’s not in the frame, but is somewhere.” If we look hard enough, perhaps we’ll find it. What and where is Rexer’s punctum? In an autobiographical—fictional, we hope—vignette about “B—not her real name,” a cipher, an unnamed young woman whom he exploited decades ago “as an au pair. You could call it that, but we didn’t pay her a wage. She lived in our house and took care of our two daughters. She was studying photography and working as a studio assistant for a photographer who was also a gallerist.” As Rexer watches his unpaid domestic servant slowly descend into mental illness, he notes B’s “strange relationship with us” as well as with her employer, who “needs a writer, she said. You could do that right? You could help him. I’ll put you in touch.” B encouraged Rexer, for whom her introduction inspires one of his origin stories: “That, simply, changed my life.” Remarking B’s increasingly eccentric behavior, Rexer reverts to cliché: “B was obsessed with Diane Arbus, her sense that other people were truly alien. Or, she was interested only in people who struck her that way, the others didn’t exist.” Rexer speaks for B, determines her interests, projects her solipsism. She gave him a photograph that he never displayed because “it would have been like hanging a diploma in a dentist’s office. A trauma diploma: I survived.” Rexer endured whatever anguishing bruxism B may have provoked in him. Not so fortunate was B, whose photographs “were bad but, of course I still remember them vividly,” and whom the gallerist thought “was a genius.” B became a bag lady “dressed in a black tentlike skirt, wrapped in black scarves and a turban. She pushed a walker that she used like a station wagon, loaded with books, papers, water bottles.” B’s tale is as tragic as it is not uncommon. By confessing to B’s exploitation and providing a textbook example of B’s othering, Rexer confirms society’s indifference to its most vulnerable. It’s not Barthes. “It’s the 90s,” a Law and Order rerun reminds us, “People play rough.”

Keeper of the Hearth reviewers also wear both metaphysical and sensualist hearts on their sleeves. Writing as publicists, they enrich their reviews with information about the images such as title, date, medium, etc. that the book neglects to share with us. Snowy evergreens rendered in faded and flat pink monochrome [48] stand in “Winter Garden, Unfixed, 2017. Unfixed contact print on expired Kodak paper.” With its chemically interrupted processing and printed on paper past its expiration date, its staining and discoloration will increase unpredictably over time as if by magic; eventually Winter Garden, Unfixed will wilt beyond recognition. In effect, the referent passes from the trees to their unfixed photographic deterioration, an eventuality ebbing away in tandem with their actual destruction due to climate change. Without the caption, the picture instant replays an indecisive moment found in countless vernacular photographs everywhere. All studium. Where’s the punctum? With comprehension of the practice informing its conceptualization, Winter Garden, Unfixed metaphorizes a life cycle writ large. (Could Rexer be right? Are we all photographs now? “Everything is a photograph,” Saul Leiter suggested.) “Thus,” writes Suzanne Révy with a Barthesian turn of phrase that ontologizes Rexer’s notion of photography out of frame into a punctum, invisible like all puncta, “unique moments are translated from traces of light and shadow into the essence of existence beyond our physical presence.” We feel it, like emotional weather, in the dark. We can touch it too. Portraying the invisible as palpable, Sabrina Mandanici acknowledges “the book’s premise of picturing the unseen and, therefore, the unknown. Perhaps a more visceral response to this very premise is prompted in [a] set of images that approach invisibility as something tactile.” And we can hear it. Noting with a musical metaphor Keeper of the Hearth’s “central idea of invisibility, of unseeing and unknowing,” Joanna L. Cresswell sees a symphony: “The edit comes to a sort of shimmering crescendo about half way through the book, with a flurry of images of mother figures appearing as just blinding light or white space….” Blind, we cannot see it. Can we speak it? What’s the punctum? Barthes and his mother “supposed, without saying anything of the kind to each other, that the frivolous insignificance of language, the suspension of images must be the very space of love, its music.” [72] If in any way we are enamored, should we remain silent and be thought a fool, or speak out and remove all doubt?

Eschewing sensual metaphysics for self-promotion, critics Sean O’Hagan and Jörg M. Colberg justify their contributions to Keeper of the Hearth rather than allow the discovery of their offerings without mediation. In his “flea market find” O’Hagan sees “in my mind at least, a portrait of the young Henriette” enlivened by a quote of “pure Barthes, astute and playful.” After interviewing other artists who submitted work, the reviewer reaches a rhetorical conclusion, wondering “if Camera Lucida’s importance attests above all to the power of words to evoke the ineffable in ways that photography simply cannot.” Where’s the punctum now? Having found “a set of photographs in a flea market in Budapest,” Colberg “gently worked them over on the computer” and submitted the one that “ended up sticking with me more than all the others” showing “a woman posing in a snowy landscape, and in the background there was this haunting spectral apparition — at least that’s what it looked like.” Who among us has not seen a ghost? More spooky than Cousin Itt stalking someone in the snow, however, will be Colberg’s surprise that “it is possible in photoland to make a collective project that ends up having a lot of meaning.” Is ineffectuality the default, like an entrenched academic protocol? So be it. Colberg frequently criticizes photoland — a polyvalent locus of an aesthetic, ideological, political, and socio-economic photography industry, “a vital tool to prop up globalised neoliberal capitalism,” as he declared in his 2020 essay about photography’s hypothetically neoliberal realism — for its willful production of consumer propaganda informed by racism, sexism, and xenophobia, weaponized with bigoted misrepresentation deployed to disempower already disenfranchised communities. Expensive, limited edition photography books function as both symbols of and collateral damage by photoland’s excesses, typified in part by large format negative space in which smaller images inhabit tiny islands on two-page oceans as specular reflections of privilege. Impartiality requires striving for objectivity unimpeded by conflict of interest. Given that “photographers and publishers make books for other photographers and wealthy collectors,” claims Colberg, and bank on “the elitism, the catering to the wealthy and subsequent production of luxury items, the endless repetition of utterly tired conventions,” his phlegmatic enthusiasm for Keeper of the Hearth cheers like an affectation.

Celebrating cheeky partiality we find artist and curator Efrem Zelony-Mindell,2 for whom the “sentimentality of the medium of photography is detestable.” What will be more sentimental than an artbook of photographs inspired by one no one has ever seen? (To mythologize, or not to mythologize? Or, as Barthes asked in his preface to Mythologies, “is there a mythology of the mythologist?”) What’s important is Keeper of the Hearth’s lesson for “creative kooks just trying to grasp onto a semblance of what is capable in the world” demonstrating the unique potential of authentic collaborations, when everyone strives together to animate a unique idea. “Here already from the very beginning England’s heart shines,” admires EZM. “She wishes to create a network and community of colleagues banded together to interpret ideals of love, responsibility, comfort, and most importantly care taking.” All these themes unfold among the dozens of old family pictures in Keeper of the Hearth; still, beyond its pages EZM learns that “something otherworldly is embodied in theory and ideology … what shines through is a commitment to community, discourse, and surrender.” From the collective emerges an energized expression of individuality. “This form of surrender is to others’ ideas and others’ instincts,” EZM attests, “which allows a bigger picture of camaraderie and a new form of self described memorial to those we love to emerge.” Does an ideologically therapeutic conformity inform Keeper of the Hearth, where community members memorialize one another even as they delude themselves into believing, with Barthes, that they can essentialize photography with a visual synecdoche? And this delusion, does it not act as a stimulant, even a hallucinogen, in their search for photography’s punctum?

Defendit numerus. Community is empowering. “I knew early on I didn’t want it to be solitary,” England told Aline Smithson, who contributed a picture and promoted the book on her online platform. “I didn’t feel I had the ability to talk about the winter garden photograph on my own, it would have felt disingenuous….” However intimidating Camera Lucida may appear to those vulnerable souls daring to decipher Barthes’ text, to collaborate, to allow others to enhance one’s artistic and curatorial vision, is to renounce the disingenuity of egocentrism. “We thrive in a kind and generous community of creative minds,” England applauds Keeper of the Hearth’s contributors. As a solitary interpretative act, editing—evaluating—their contributions also risks duplicity, as England told O’Hagan: “Forefront in my mind was the question: ‘Who am I to say what constitutes a valid or worthwhile interpretation of Barthes’s Winter Garden Photograph?’ I didn’t weed anything out and would have felt disingenuous doing so.” With her gardening metaphor, England grants her artists their higher educated entitlement to overdetermine how well their contributions may flourish with Camera Lucida, and she paraphrases Barthes’ textual raison d’être even as her path diverges from that of the master. “As for my own winter garden photograph,” England reflects, “dare I show it, describe it, or both – or neither? … I decide to reveal rather than conceal it. I don’t mind that it may not hold meaning for anyone else. It is for me.” For artist Nicholas Muellner, as it is for Barthes, punctum is too personal to share. Like England concerned about artifice, Muellner clarifies in ethical terms and inverted commas his refusal to submit an image: to “‘show’ a ‘Winter Garden photograph’ of my own … feels like a betrayal of both his argument and my own singular experience. And when I try to conceive of an image that refuses, that seems coy or insincere.” Why does the quest to interpret Barthes and Camera Lucida, whether alone or with others, in secret or in public, provoke questions about duplicity and insincerity? “I don’t know Barthes’ work,” artist, publisher, and NFT entrepreneur Kris Graves divulged during a panel discussion about the project, “I’ve never read the books. I didn’t know what Odette was talking about.” Does Graves’ picture, submitted to and included in Keeper of the Hearth despite his ignorance of Barthes, epitomize the normalization of photoland’s self-promoting cynicism?

A collection of images submitted by “a who's who of today's photo scene” and curated to signify, to borrow a phrase from contributor Doug DuBois, “the graceful, open-ended meaning of ‘Untitled’” is nothing if not resolutely Barthesian. “Some artists couldn’t help themselves,” Colberg grumbles, “and sent in an image that’s very obviously just their regular work….” True enough; sprinkled among the snapshots are sensitive portraits and sophisticated constructions exhibiting creative discernment and mastery of craft. To assume comparable artistic acumen guiding all the vernacular and pseudo-vernacular imagery in Keeper of the Hearth requires an act of faith that Barthes would not have advocated. A “specific photograph, in effect,” Barthes sermonizes, “is never distinguished from its referent (from what it represents) … it is not impossible to perceive the photographic signifier (certain professionals do so), but it requires a secondary action of knowledge or of reflection.” [5] Distinguishing between amateur and professional photographers, Barthes grants to the latter the power to see metaphor in photographs; for everybody else it’s catch-as-catch-can. In opposition to Barthes’s oddly outmoded opinion, England posits that artists and viewers are equally responsible for connecting with art. “But the potential for a photograph to create connections for a viewer depends as much on that viewer’s mental activity as it does on the material or sensorial qualities of the image,” England proposed in her doctoral thesis. “A photograph is a cue; it can only trigger a richer, fuller picture if a viewer has imagination, information, and a desire to recollect.” Be that as it may, without editorial direction, Keeper of the Hearth is blind to a discrete aesthetic vision and suffers from an acute case of portfolio syndrome. No unifying narrative develops beyond that of randomized impermanence mashed up with glorious indeterminacy. The sum is not greater than its parts.

Or is it? Like alms on an altar sacrificing vernacular studium for phantasmagorical punctum, Keeper of the Hearth remains a cultural artifact, a snapshot of the academic art photography industry that produced it, and a footnote in the commercial and intellectual history of Barthes’ immortality.

Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes, Hill and Wang, translation by Richard Howard ©1981, foreword by Geoff Dyer ©2010. Page numbers in brackets.

UPDATE Dec. 19, 2022

As reported by the Department of Justice on 16 December, Efrem Zelony-Mindell was arrested by the FBI and charged with “attempted enticement of one minor boy in Manhattan, New York, and possession and distribution of child pornography.” It is understandable that his interviewers, as well as the dozens of artists whose work EZM curated into his books and exhibitions, feel betrayed. Subsequently, the Humble Arts Foundation, Lenscratch, the Strange Fire Collective, Vogue, and many other organizations, including his publisher Gnomic Book, have deleted without notification their features about and interviews with Zelony-Mindell. The link to his writing quoted in this review is now broken.

I quite like this; it's mostly well-written, where it's not overwritten with showboaty rhetorical jargon. I suppose that's an 'About Barthes' thing, I've seen it before, lots. Academia, eh? I feel I already have a pretty good handle on pop-culture Barthes, having never actually read him (I tend to skate over texts, avoiding the thin ice). Always fun to get a new, thoughtful and erudite take!

The ostensible subject of this one, "Keeper of the Hearth" is unclear until almost half-way through, where it is named. Ok...

“Here already from the very beginning England’s heart shines,” admires EZM. “She wishes to create a network and community of colleagues banded together to interpret ideals of love, responsibility, comfort, and most importantly care taking.” England? WTF? Oh, the editor.

The gatekeepers. The emergents. The holy lucky ones. The smoothies. The ones who lend the moon a beam. The ones who defer to degrees of lockstep. The bald cynicism which informs my viewfinder. Thank you, Mr. McClintock. Your essay underlines the lubrication of a pervasive machination, which thrives on rehashing contemporary photographers the world needs to watch.